Interview with Marek Šuppa: insights into RoboCupJunior

A RoboCupJunior soccer match in action. In July this year, 2500 participants congregated in Bordeaux for RoboCup2023. The competition comprises a number of leagues, and among them is RoboCupJunior, which is designed to introduce RoboCup to school children, with the focus being on education. There are three sub-leagues: Soccer, Rescue and OnStage. Marek Šuppa serves […]

A RoboCupJunior soccer match in action.

A RoboCupJunior soccer match in action.

In July this year, 2500 participants congregated in Bordeaux for RoboCup2023. The competition comprises a number of leagues, and among them is RoboCupJunior, which is designed to introduce RoboCup to school children, with the focus being on education. There are three sub-leagues: Soccer, Rescue and OnStage.

Marek Šuppa serves on the Executive Committee for RoboCupJunior, and he told us about the competition this year and the latest developments in the Soccer league.

What is your role in RoboCupJunior and how long have you been involved with this league?

I started with RoboCupJunior quite a while ago: my first international competition was in 2009 in Graz, where I was lucky enough to compete in Soccer for the first time. Our team didn’t do all that well in that event but RoboCup made a deep impression and so I stayed around: first as a competitor and later to help organise the RoboCupJunior Soccer league. Right now I am serving as part of the RoboCupJunior Execs who are responsible for the organisation of RoboCupJunior as a whole.

How was the event this year? What were some of the highlights?

I guess this year’s theme or slogan, if we were to give it one, would be “back to normal”, or something like that. Although RoboCup 2022 already took place in-person in Thailand last year after two years of a pandemic pause, it was in a rather limited capacity, as COVID-19 still affected quite a few regions. It was great to see that the RoboCup community was able to persevere and even thrive throughout the pandemic, and that RoboCup 2023 was once again an event where thousands of robots and roboticists meet.

It would also be difficult to do this question justice without thanking the local French organisers. They were actually ready to organise the event in 2020 but it got cancelled due to COVID-19. But they did not give up on the idea and managed to put together an awesome event this year, for which we are very thankful.

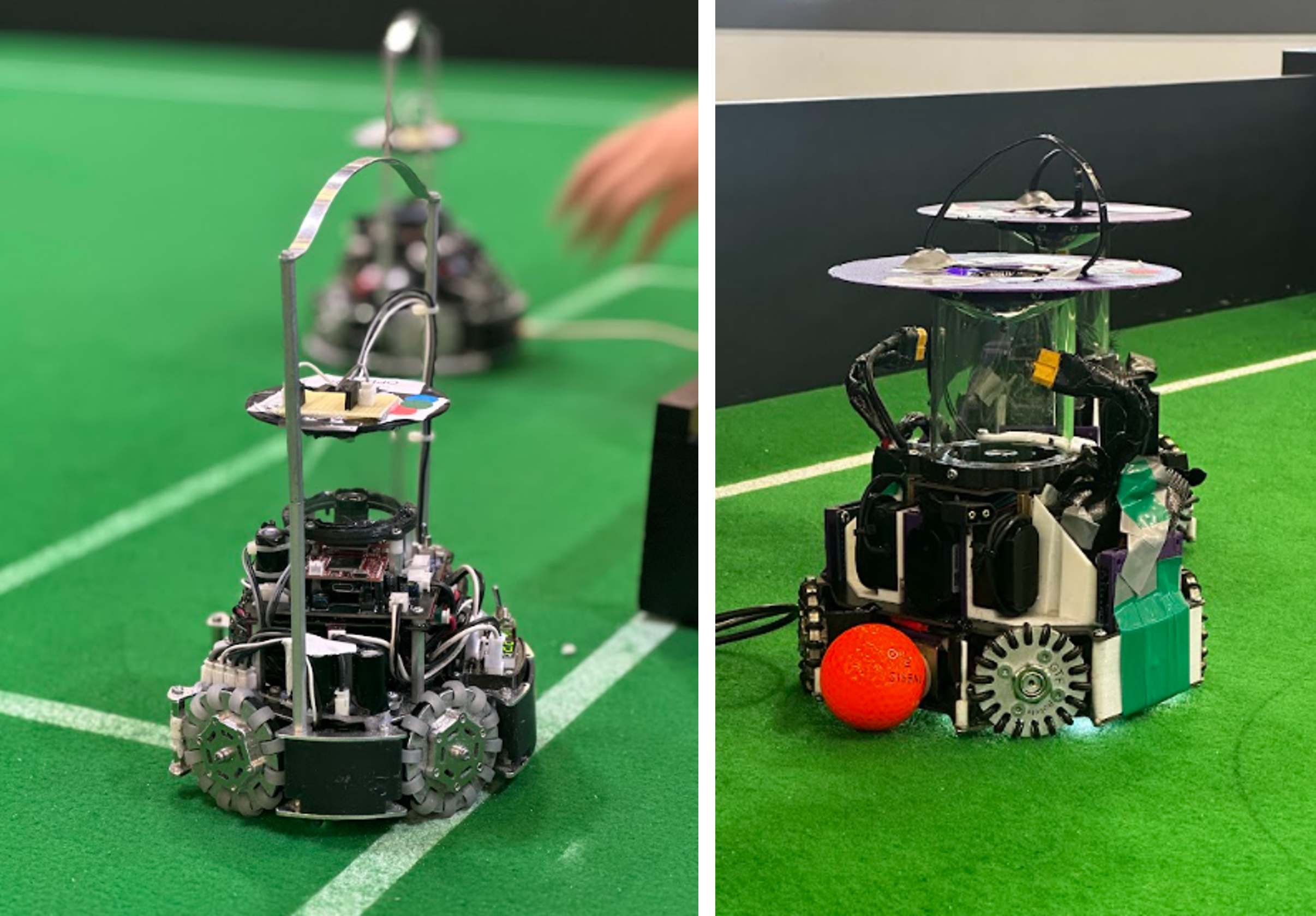

Examples of the robots used by the RoboCupJunior Soccer teams.

Examples of the robots used by the RoboCupJunior Soccer teams.

Turning to RoboCupJunior Soccer specifically, could you talk about the mission of the league and how you, as organisers, go about realising that mission?

The mission of RoboCupJunior consists of two competing objectives: on one hand, it needs to be a challenge that’s approachable, interesting and relevant for (mostly) high school students and at the same time it needs to be closely related to the RoboCup “Major” challenges, which are tackled by university students and their mentors. We are hence continuously trying to both make it more compelling and captivating for the students and at the same time ensure it is technical enough to help them grow towards the RoboCup “Major” challenges.

One of the ways we do that is by introducing what we call “SuperTeam” challenges, in which teams from respective countries form a so-called “SuperTeam” and compete against another “SuperTeam” as if these were distinct teams. In RoboCupJunior Soccer the “SuperTeams” are composed of four to five teams and they compete on a field that is six times larger than the “standard” fields that are used for the individual games. While in the individual matches each team can play with two robots at most (resulting in a 2v2 game) in a SuperTeam match each SuperTeam fields five robots, meaning there are 10 robots that play on the SuperTeam field during a SuperTeam match. The setup is very similar to the Division B of the Small Size League of RoboCup “Major”.

The SuperTeam games have existed in RoboCupJunior Soccer since 2013, so for quite a while, and the feedback we received on them was overwhelmingly positive: it was a lot of fun for both the participants as well as the spectators. But compared to the Small Size League games there were still two noticeable differences: the robots did not have a way of communicating with one another and additionally, the referees did not have a way of communicating with the robots. The result was that not only was there little coordination among robots of the same SuperTeam, whenever the game needed to be stopped, the referees had to physically run after the robots on the field to catch them and do a kickoff after a goal was scored. Although hilarious, it’s far from how we would imagine the SuperTeam games to look.

The RoboCupJunior Soccer Standard Communication Modules aim to do both. The module itself is a small device that is attached to each robot on the SuperTeam field. These devices are all connected via Bluetooth to a single smartphone, through which the referee can send commands to all robots on the field. The devices themselves also support direct message exchange between robots on a single SuperTeam, meaning the teams do not have to invest into figuring out how to communicate with the other robots but can make use of a common platform. The devices, as well as their firmware, are open source, meaning not only that everyone can build their own Standard Communication Module if they’d like but also that the community can participate in its development, which makes it an interesting addition to RoboCupJunior Soccer.

RoboCupJunior Soccer teams getting ready for the competition.

RoboCupJunior Soccer teams getting ready for the competition.

How did this new module work out in the competition? Did you see an improvement in experience for the teams and organisers?

In this first big public test we focused on exploring how (and whether) these modules can improve the gameplay – especially the “chasing robots at kickoff”. Although we’ve done “lab experiments” in the past and had some empirical evidence that it should work rather well, this was the first time we tried it in a real competition.

All in all, I would say that it was a very positive experiment. The modules themselves did work quite well and for some of us, who happened to have experience with “robot chasing” mentioned above, it was sort of a magical feeling to see the robots stop right on the main referee’s whistle.

We also found out potential areas for improvement in the future. The modules themselves do not have a power source of their own and were powered by the robots themselves. We didn’t think this would be a problem but in the “real world” test it transpired that the voltage levels the robots are capable of providing fluctuates significantly – for instance when the robot decides to aggressively accelerate – which in turn means some of the modules disconnect when the voltage is lowered significantly. However, it ended up being a nice lesson for everyone involved, one that we can certainly learn from when we design the next iterations.

The livestream from Day 4 of RoboCupJunior Soccer 2023. This stream includes the SuperTeam finals and the technical challenges. You can also view the livestream of the semifinals and finals from day three here.

Could you tell us about the emergence of deep-learning models in the RoboCupJunior leagues?

This is something we started to observe in recent years which surprised us organisers, to some extent. In our day-to-day jobs (that is, when we are not organising RoboCup), many of us, the organisers, work in areas related to robotics, computer science, and engineering in general – with some of us also doing research in artificial intelligence and machine learning. And while we always thought that it would be great to see more of the cutting-edge research being applied at RoboCupJunior, we always dismissed it as something too advanced and/or difficult to set up for the high school students that comprise the majority of RoboCupJunior students.

Well, to our great surprise, some of the more advanced teams have started to utilise methods and technologies that are very close to the current state-of-the-art in various areas, particularly computer vision and deep learning. A good example would be object detectors (usually based on the YOLO architecture), which are now used across all three Junior leagues: in OnStage to detect various props, robots and humans who perform on the stage together, in Rescue to detect the victims the robots are rescuing and in Soccer to detect the ball, the goals, and the opponents. And while the participants generally used an off-the-shelf implementations, they still needed to do all the steps necessary for a successful deployment of this technology: gather a dataset, finetune the deep-learning model and deploy it on their robots – all of which is far from trivial and is very close to how these technologies get used in both research and industry.

Although we have seen only the more advanced teams use deep-learning models at RoboCupJunior, we expect that in the future we will see it become much more prevalent, especially as the technology and the tooling around it becomes more mature and robust. It does show, however, that despite their age, the RoboCupJunior students are very close to cutting-edge research and state-of-the-art technologies.

Action from RoboCupJunior Soccer 2023.

Action from RoboCupJunior Soccer 2023.

How can people get involved in RCJ (either as a participant or an organiser?)

A very good question!

The best place to start would be the RoboCupJunior website where one can find many interesting details about RoboCupJunior, the respective leagues (such as Soccer, Rescue and OnStage), and the relevant regional representatives who organise regional events. Getting in touch with a regional representative is by far the easiest way of getting started with RoboCup Junior.

Additionally, I can certainly recommend the RoboCupJunior forum, where many RoboCupJunior participants, past and present, as well as the organisers, discuss many related topics in the open. The community is very beginner friendly, so if RoboCupJunior sounds interesting, do not hesitate to stop by and say hi!

About Marek Šuppa

|

Marek stumbled upon AI as a teenager when building soccer-playing robots and quickly realised he is not smart enough to do all the programming by himself. Since then, he’s been figuring out ways to make machines learn by themselves, particularly from text and images. He currently serves as the Principal Data Scientist at Slido (part of Cisco), improving the way meetings are run around the world. Staying true to his roots, he tries to provide others with a chance to have a similar experience by organising the RoboCupJunior competition as part of the Executive Committee. |